Each summer, Oxford Contact Dance has organised Dance in the Park – where we dance contact improvisation outside. This year’s Dance in the Park is going to be a bit different due to COVID19. We won’t be dancing with our bodies in contact but physically distanced (‘social distancing’) and there must be no more than six dancers – by law (in England). Let’s investigate and research this configuration – six people, two metres apart. Let’s dance six two (#dance62)!

In this article, I use the term physical distancing rather than social distancing. When we dance together, it’s social dancing. But the distance between our dancing bodies must be two metres or more to meet the UK Government’s COVID19 guidance (June 2020) and to reduce the risk of infection. Dancing alone would indeed be ‘socially distanced’ dance. But here, I describe dancing together albeit physically distanced by two metres or more!

Re-imagining dance – research and investigate

When I see this footage of contact improvisation from 1972 and I listen to the commentary by Steve Paxton- one of the pioneers of contact improvisation – then I am reminded that contact improvisation is both an investigation and a research.

“I’m examining the passage from up to down.”

Dancer Steve Paxton narrating film Contact Improvisation 1972 (above)

Now – in summer 2020 when there is an pandemic of coronavirus/COVID19, we have time for research, investigation and innovation – a time to re-imagine our dance practice ‘contact improvisation’ to include physical distancing.

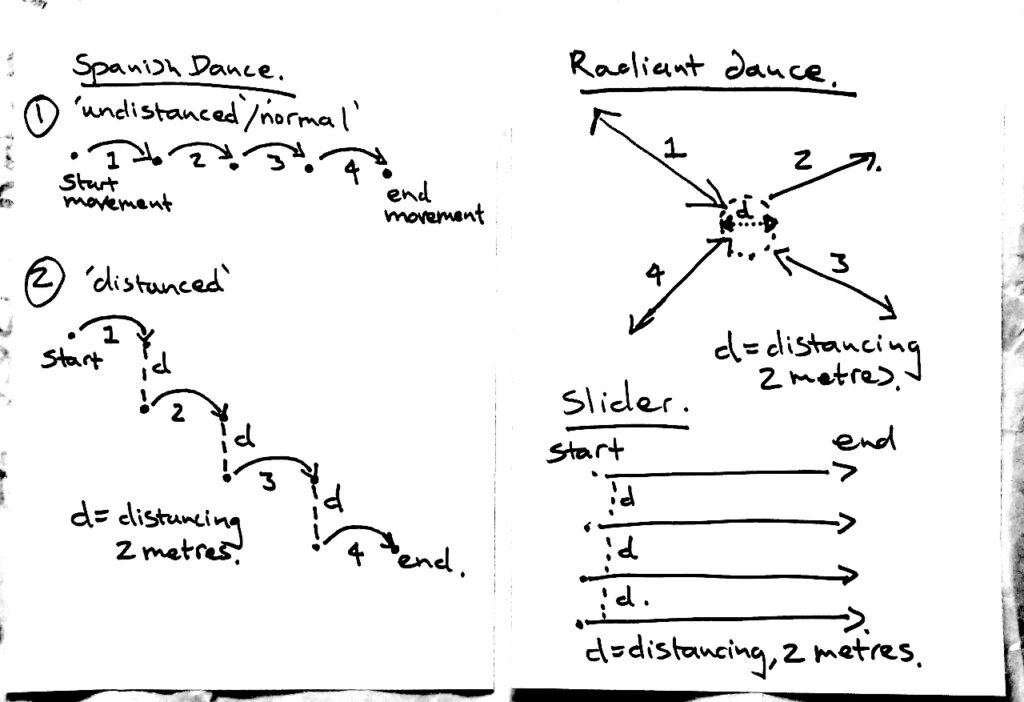

Spanish Dance

The dancer and choreographer Trisha Brown created a dance sequence entitled ‘Spanish Dance’. The score (composition) is very simple: dancers stand in a line facing the back of each other; the dancer at the end moves and travels such that eventually they come into contact with the back of the dancer in front of them and they stop dancing; the next person in line does the same – contacting the back of the dancer in front of them; eventually all the dancers have moved and contacted the dancer in front until the last dancer – at the front – moves and/or travels to become still. End.

In essence, it’s like a pack of dominoes where one falls onto another causing them all to fall in a sequence. You can see a dance inspired by Trisha Brown’s Spanish Dance below at a session of Oxford Contact Dance (2017).

Here’s a second example from the 2017 session at Oxford Contact Dance (You Tube)

We can easily physically distance the Spanish Dance. Imagine the dancers are not aligned, and rather than using contact – touch – to ‘pass-on’ the movement, we could use sight, sound – all the senses other than touch! The sketches below (Spanish Dance Re-imagined) illustrates this. It seems overly simplistic but it’s a place from which we can start and explore – the first steps of a research – rather than the end.

Geometry of dance

In the park – outside, we have lots of space for a remodelled ‘Spanish Dance’. We can examine its geometric form and shape. In the original ‘Spanish Dance’ then the shape is a line. But we can have many shapes – a triangle with a trio of dances, a hexagonal shape (circle) with six dancers. We take a line for a walk – to misquote Miro.

Shapes formed from assembles of distanced dancing bodies can be complex and beyond simple geometries. For example, six dancers might be repulsed from each other, moving outward to form a star. The Spanish Dance is much like a Mexican wave in its mechanics. It’s almost a dance automaton as one dancer falls into another. We can investigate – in dance – the movement composition as well as its spatial composition.

Investigating space

“all points of the kinesphere can be reached by simple movements, such as bending, stretching, and twisting, or by a combination of these.”

Rudolf Laban

When we dance contact improvisation then it’s said we dance in a ‘kinesphere’ (Kinesphäre). But when we dance in a physically distanced way then we dance with the space outside of the kinesphere – the ‘exo-sphere’ – as we might say. Remember those art classes where you’d draw ‘negative space’ to create a form? Perhaps that’s the challenge here?

Contact what, where!!?

Often we start dancing Contact Improvisation with eye contact before we move into physical contact – so here’s the idea of contact without touch. Sound is another landscape which we inhabit and it too can be a contact between dancers. A fluid one, as water surrounds all who swim in it. Calls and sounds, the utterance of words can be another way to dance with contact, as is gesturing to each other.

Or maybe there’s a sense of presence in our dancing – when someone is close but not actually touching. Peripheral vision gives us part of this, and indeed this vision is especially responsive to movements. We might say, there is a sense of contact – and indeed what is touch but a sense of something. There is ‘outer-contact’ (äußeren Kontakt?).

We have the idea of a ‘point of contact’ between bodies dancing in contact. In our physically distanced dance then the ground on which we dance, is a shared contact surface. We stand, we fall and move on it. We dance in gravity. There’s a surface which we inhabit even when physically distanced from another body: a shared surface for contact.

Sculpting with space and form

‘Hold your hands out and imagine you are carrying a ball’ – how many times have you heard that said in a dance class! There’s the idea of enclosing space between our arms although often when we’re asked to imagine holding a ball (an imagined form), it’s to shape our bodies in some way rather than to feel or enclose space. We can touch the surface of this ‘imagined form’ with more than our hands – our backs, our shoulders, our legs, feet, etc. Our bodies move on the imagined form and be in contact with it.

We can use the idea of sculpting space – together – by moving and travelling on its surface. For example, in a dance ensemble then the movement of the dancers on the ‘surface of a space’ – a space/void which is shared and shaped by all, creates this form. It could be movement which is fluid or indeed static (non-movement); and perhaps a shape which is ever changing and malleable – the space between.

An idea of the ‘space between’ is one which was explored in our In Between dance (2019) although this involved physical contact. In this dance, the space was between the performers – the music of the musicians and the movement of the dancers. Space is both a concept as well as a physical experience.

Narratives can help to inform our imagination and creative practices. When a planet orbits a sun then we know there is a gravitational connection. The behaviour of the our bodies shows us as much – we can also feel gravity. The behaviours of bodies and movement – presented to others – itself creates connection and a sense of contact. An idea which Steve Batts (via Robert Anderson) describes as the architectures of dance (2017).

Investigating ‘outer-contact’

Dancing contact improvisation is centred on touch and impression – the physical meeting of bodies and ‘sharing weight’. A ‘playful physics’ as dancer Robert Anderson says. Now we have an opportunity – thrust upon us – to investigate and research all that is outer-contact in the exo-sphere. In practice, contact improvisation has always included this outer-contact but now – perhaps for a limited period, it will only be that. Eventually, it will be folded back into the corporeal movement practice which we love, and which we know as contact improvisation.